Discover more from From Symptoms to Causes

What Can We Learn from the Faroe Islands?

The Faroese authorities never fell prey to the irrational fear and scare tactics that unfortunately prevailed for the most part in the rest of the world.

Mid-way between Iceland and Scotland, the Faroe Islands are a country of approximately 50,000 people. The Faroe Islands are part of the kingdom of Denmark, but self-governing for the most part. The Faroese are of Scandinavian and Celtic descent and speak their own language which is very close to Icelandic.

For an Icelander, reading Faroese is relatively easy, but the pronunciation is very different. The seafood industry is by far the largest sector in the Faroe Islands. The Faroese are a close-knit community, proud of their history and traditions, famous for their ring dance, locally called Faroese dance (Föröyskur dansur), which has lived on ever since the Middle Ages, while mostly disappearing in the rest of Europe.

The approach taken by the Faroese authorities at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was starkly different from that of most neighbouring countries. The Government did not issue any lockdown mandates, only recommendations, similar to the approach Sweden took. One of the most vocal opponents of COVID-19 restrictions in the Faroe Islands is musician and events planner Jón Tyril. Jón wrote to several ministers, members of the Faroese parliament and others in the political establishment at the outset. “I urged them to not adopt the same ‘epidemic law’ that Denmark had put in place, and which gave extended powers to the ministry of health and the police, to avoid mandates and forced restrictions, but rather to build on cooperation and trust,” Jón says.

This path of recommendations became the route they took.

Government offices and some public services were closed for a while and schools were closed for a few weeks at the start of the pandemic only. After that they remained open, even despite rising pressure for school closures towards the end of 2021. “There was strong pressure on closing schools a week early before last Christmas, but I did not agree to this,” Minister for Education Dr. Jenis Av Rana said in a recent interview with Icelandic online newspaper Frettin.

“It is important for children to keep their freedom and lead a normal life, this is important for their development and well-being. There was a heated debate on this amongst the Cabinet members. At first I encountered strong opposition, but in the end we agreed on this,” the Minister said. Dr. Rana, who is also the Minister of Foreign Affairs, along with Education and Culture, decided not to get vaccinated against COVID-19. A practising medical doctor for 35 years, the Minister said using vaccination to counter the spread of coronaviruses is futile. Events have clearly proved him right.

Frettin also interviewed Kaj Leo Holm Johannesen, former Prime Minister and currently Minister for Healthcare. The Minister said it was still not clear if people registered as dead from COVID-19 actually died from the disease or from other causes. “We cannot claim anyone has died from Covid, all we know is that people have died diagnosed with Covid. An autopsy is needed to verify the cause,“ the Minister told Frettin reporters.

During the initial lockdown in 2020 and into the summer, care homes and hospitals were totally closed to visitors. The decision to open up was made by the Heilsuverkid, the Faroese version of the NHS, and Kommunufelagid, which is the municipalities association together with the National Council on Ethics.

The policy statement claims the level of isolation resulting from continued closures was far too harmful to be justifiable. Instead people were urged to take the utmost precautions when visiting. As in most other countries, the Faroese epidemic committee pushed for mask mandates, but unlike most other countries the Government decided against them.

Stricter lockdowns in Iceland made no difference

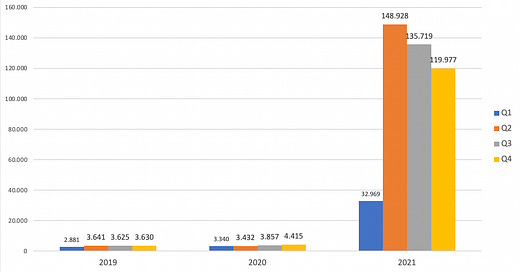

It is instructive to compare the development of the COVID-19 pandemic during its first year (before vaccines were available) in the Faroe Islands and neighbouring Iceland, another tiny nation, very similar in terms of culture and living standards. While Iceland implemented strict measures (despite recent claims to the contrary), closed schools, intermittently closed bars and restaurants and hairdressers and other personal service businesses, and put strict limits on gatherings, the spread of infections remained largely the same in the two countries throughout those first 12 months.

By the end of February 2021, confirmed cases in the Faroe Islands were just under 14,000 per million and deaths were at 20 per million. In comparison, Iceland had 16,000 cases and 80 deaths per million during the first year of the pandemic.

In Iceland, the Government Ministers took pride in delegating all decisions to the Chief Epidemiologist, the Head of the Directorate of Health and a police officer, who formed a committee of three, “the troika”, which practically dictated the response to the pandemic. Until very recently, the Minister for Healthcare and the Government simply rubber-stamped their decisions every time.

Judging from discussions with locals and recent interviews with Faroese politicians, it looks as if a key differentiator between the Faroese approach and that taken by most other countries is that in the Faroe Islands it was the Government that took direct responsibility for decisions and often went against the recommendations of the epidemic committee.

Decisions were based on broader considerations than just the number of infections. It also looks as if they were fact-based to a larger extent than elsewhere. Schools were kept open, both because of the importance of avoiding disruption of children‘s education and also based on the low risk to children and low infection rates among mostly asymptomatic children. Mask mandates were never introduced, as the authorities never saw any solid evidence masks would limit transmission. “Masks do not prevent infections,“ Dr. Rana told Frettin‘s reporters. “They are not designed for this, but to protect physicians and patients in the operating room,” he said.

It was only in late 2021, with a large surge in cases and an outbreak at a care home that suddenly drove up deaths, that the Government bowed to public pressure to impose somewhat stronger restrictions. In November, a Covid-pass (vaccine passport) was allowed, but not mandated, only to be discontinued again about a month later. “This was not a good move,” Jón Tyril says. “In a small community like ours, refusing friends and family members entry to establishments can easily ruin social bonds.” A petition against the pass was started immediately and had reached 1,500 signatures when the measure was abolished.

All Covid recommendations and restrictions were lifted in the Faroe Islands at the end of February 2022, despite a strong rise in cases during the previous weeks.

The success of the Faroese approach shows how a pandemic can be dealt with without imposing strict lockdowns and mandates. The comparison between the Faroe Islands and Iceland strongly indicates the futility of mandatory lockdowns. Avoiding mandates is also likely to have helped avoid the friction seen in many other countries.

In the words of Jón Tyril:

“I think that we had less of a divide in the public than many other nations. We did not have pro- and anti-maskers, since there were no mask mandates. We did have a certain level of pro- and anti-vax divide, but the Government never went in and talked down to those who chose not to get vaxed, as we saw in other countries like Denmark, France, Italy, Canada. In fact, they kept saying that this was voluntary and nobody should feel forced to take the vax. So, the pandemic was divisive, especially because we are a very closely knit society, but my impression is that we were not nearly as divided as countries with mandates, long standing Covid passes and hard rhetoric from the leaders.”

The Faroese authorities never fell prey to the irrational fear and scare tactics that unfortunately prevailed for the most part in the rest of the world. Instead, they showed the self-confidence, the respect for fact-based decision-making and consideration of the broader picture needed when confronted with an acute situation.

Finally, what the Faroese approach shows us is how important it is that elected representatives take direct responsibility for all decisions, instead of delegating them to officials without any democratic accountability. This might in fact be the most important lesson we can learn from the tiny Faroese nation.

Subscribe to From Symptoms to Causes

A critical view of the world