Discover more from From Symptoms to Causes

How Common Sense Prevailed in Sweden

The success of Sweden may be viewed as a victory for the cool-headed utilitarianism of the sober and conscientious public health bureaucrats, at all times keeping their eyes on the big picture.

First published in The Conservative Woman - for republishing, please refer to the original.

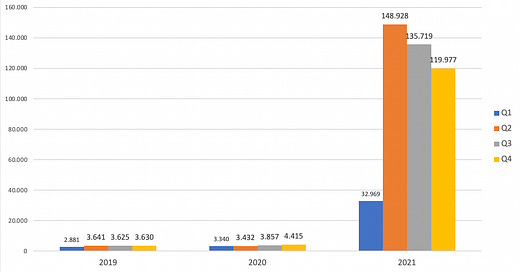

THE Swedes are to be saluted for standing up to Project Fear. Three years into the pandemic, their lone stand has been proved right and everyone else’s wrong. They have sustained much less economic damage than the rest of Europe, but the critical proof is their lowest excess mortality over those three years. For those who have gone on and on about Sweden’s strategy killing people, this is really a slap in the face, isn’t it?

The question which remains is why Sweden reacted to the virus in such a fundamentally different way, and how they dared withstand the global groupthink. This is what Swedish author and journalist Johan Anderberg documents in his account of the first year of the pandemic, The Herd – How Sweden Chose Its Own Path Through the Worst Pandemic in 100 Years, first published in Swedish two years ago. It stands the test of time and warrants reading, or rereading, today.

Anderberg’s research is meticulous, the narration highly detailed when needed. Written in light journalistic style, building tension at the right moments, The Herd is a page-turner indeed. It offers the reader deep insight into the chain of events and sheds light on the personalities and experience of the key players, their relationships and the strife in the background.

While many readers will be familiar with the name of Swedish Chief Epidemiologist Anders Tegnell, revered by many but hated by others, fewer may know of Johan Giesecke, Tegnell’s predecessor and mentor, brought in as an adviser early on, who according to Anderberg might be seen as the true key decision-maker. Fewer still will have heard of Kerstin Hessius, powerful CEO of the Third National Swedish Pension Fund, who right at the beginning argued against lockdown, putting things into perspective: ‘No, these are not economic effects. This is not about economics, it’s about people,’ she responded when asked about the cynicism of weighing human lives against the economy in a TV interview on March 20, 2020. There was no outcry against Hessius; Anderberg suggests the Swedish had simply been reminded of their society’s long-standing priority of rational decision-making in public health, of how lives are about all lives, now and in the future, not only the ones under threat at this exact moment. It was not least because of the outlier position taken by Hessius that Giesecke and Tegnell found themselves on some kind of a middle ground.

As Anderberg explains, the Swedes are pioneers in public health and epidemiology. It was as early as 1749 that they began regularly to collect and publish population data; in the 1960s that they started to use formal cost-benefit analysis for infrastructure projects, and shortly afterwards in public health. They may be risk-averse and cautious, but they have a long-standing tradition of being guided by facts and data.

The independence of Swedish government agencies also played an important part: government ministers are forbidden to meddle directly in their decision-making. Thus, with an independent Public Health Agency, led by seasoned public servants who couldn’t care less about what others thought of them, the official line was set.

Anderberg adds perspective providing historical background. He explains Daniel Bernoulli’s smallpox calculations in the 18th century, which became the basis of modern epidemiology, John Snow’s discovery of the source of cholera in London in the 19th century, takes us back to the times of the Spanish Flu and the US swine-flu vaccination disaster of 1976.

To explain the position of Tegnell, Anderberg suggests his experience during the exaggerated swine-flu outbreak of 2009 may have played an important part. Most countries decided against mass vaccination, despite high pressure from pharmaceutical companies. But in Sweden Tegnell went for it, resulting in hundreds of people developing a serious neurological condition, narcolepsy. In the end the vaccination campaign was estimated to have saved only a handful of lives as the flu soon petered out. The lessons of the episode still bear on Sweden’s vaccine injury policy.

In many countries the predictions of Dr Neil Ferguson of Imperial College London strongly influenced the pandemic policy, as they had previously with the 2009 swine-flu outbreak, but not in Sweden. The Swedish Public Health Agency reviewed his study carefully and their conclusion was that the most important estimates on which his modelling was based were far off the mark. They were also well aware of Ferguson’s history of wildly exaggerated predictions. In 2001 he predicted 50,000 deaths from mad cow disease. In fact only 177 people died. In 2005 Ferguson warned of 150million deaths globally from bird flu. Just 455 died. In 2009 he foretold 65,000 deaths from swine-flu in the UK. The actual number was 474. So with his long history of being wrong the Swedes simply pushed Ferguson’s models aside. The question remains why a deeply flawed model concocted by a doomsayer proven wrong time after time became the cornerstone of pandemic strategies elsewhere.

As Anderberg explains, Tegnell, Giesecke and their team made mistakes. Their strong belief early on that they were on the brink of herd immunity proved faulty, leading to an underestimation of the number of deaths. They were also pessimistic regarding the arrival of a vaccine – though two years on, their instinct may be proved to be right. And there was political backlash for sure. In November 2020, as the infection rate exploded, the government stepped in, using a loophole to close bars and nightclubs, then soon afterwards more restrictions followed, though never anything close to those of most other countries.

Towards the end of the book, Anderberg sums up how his country fared during the first year of the pandemic. Deaths were up, no question, but compared with a bad flu year, such as 1993, they were not exceptional. In fact, the country, at one time dismissed by the New York Times as a ‘pariah state’ doing everything wrong, was doing much better than most of Europe over coronavirus deaths.

Most importantly, Sweden had escaped the devastation of the lockdowns, and there is little doubt this is the most important reason why now, three years after the ‘world went mad’ as Tegnell and Giesecke described it, Sweden has the lowest rate of excess deaths in Europe. This is also why Sweden has, for the most part, escaped the economic devastation and the terrible trend of declining physical and psychological wellbeing we now see almost everywhere else.

The success of Sweden may be viewed as a victory for the cool-headed utilitarianism by which this small northern country has been governed for hundreds of years. A victory for the deep-seated respect for Sweden’s sober and conscientious public health bureaucrats, at all times keeping their eyes on the big picture. In short, a victory for common sense, which most importantly turned out to be a victory for the young. Andersen’s relays Johan Giesecke’s message in an interview in late 2020: ‘It was really quite simple: his life, he argued, was less valuable than his grandchildren’s lives. And not just his grandchildren’s. All children’s lives.’

The success of Sweden is of huge importance, for it undermines the mantra that we had no choice. The Herd provides an excellent insight into the chain of events behind it.

Thanks for bringing some more attention back to the closest nation we have to a "placebo" group.

I love this sentence:

"The question remains why a deeply flawed model concocted by a doomsayer proven wrong time after time became the cornerstone of pandemic strategies elsewhere."

Yes, that question does remain ... or should remain. Why do we give such massive influence to experts who have been spectacularly wrong time and time again?

"The success of Sweden is of huge importance, for it undermines the mantra that we had no choice. The Herd provides an excellent insight into the chain of events behind it."

Thanks for a brilliant piece, informative and insightful as usual.

I just bought the Kindle edition of the book, should make great reading.

Swedens approach was truly remarkable by any standards, and a lesson for future generations, albeit their gusto for vaccination seems out of place, maybe the book has an answer.